NEUROLOGICAL DISEASES IN PETS:

Seizures in Cats

(aka: feline seizures, feline seizure disorders)

Disease Overview

Seizures are relatively common in cats and account for approximately 20% of seizure patients treated by veterinary neurologists. Unlike dogs, cats rarely have idiopathic epilepsy. In fact, more than 75% of cats with focal or generalized seizures have an identifiable underlying systemic or intracranial disease.

Most seizures in cats are caused by an underlying condition rather than primary epilepsy. Identifying the underlying cause is one of the greatest challenges in treating feline seizures.Reported causes include:

Infectious diseases

Ischemic encephalopathy

Renal disease

Hypertension

Neoplasia

Encephalitis

Polycythemia

Other systemic or intracranial factors

Although any cat can develop seizures, certain breeds, such as the Abyssinian, Bengal, and Siamese, may be at higher risk due to genetic factors. Birman cats can experience a specific type of seizure known as feline audiogenic reflex seizures (FARS), which are often triggered by certain sounds. This condition is more common in older Birmans and may be linked to genetic factors and hearing loss.

Seizures are relatively common in cats, with feline patients representing about 20% of seizure cases treated by VNIoC.

Diagnosing Seizures in Cats

After seizure activity has been controlled and the cat stabilized, diagnosis begins with a thorough neurological examination. Abnormal findings on this exam may indicate intracranial disease.

Diagnostic testing may include:

Complete blood count (CBC)

Serum chemistry panel

Thoracic radiographs

Feline viral panel

T4 testing

Urinalysis

Depending on results, further testing for infectious diseases such as toxoplasmosis or Cryptococcus may be pursued. If the underlying cause remains unclear, advanced diagnostics should be considered such as a brain MRI or CT and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions about Seizures in Cats

-

Seizures are relatively common in cats. About 20% of seizure patients treated by veterinary neurologists are feline patients.

-

Unlike dogs, cats rarely have idiopathic epilepsy. In most cases, seizures in cats are caused by an underlying medical or neurological condition.

-

More than 75% of cats with focal or generalized seizures have an identifiable underlying disease. Causes may include infectious diseases, kidney disease, high blood pressure, brain inflammation, cancer, or other systemic conditions.

-

This is determined on a case-by-case basis and depends on the underlying cause of the seizures. Further guidance should be discussed with your veterinarian.

-

The outcome depends on identifying and managing the underlying cause. Your veterinarian will guide you based on diagnostic findings.

Treating Cats with Seizures

Primary Treatment

The initial drug of choice for seizure management in cats is Phenobarbital. Cats generally tolerate this medication better than dogs.

Typical starting dose: 2 mg/kg twice daily

Dose may be adjusted to achieve a serum concentration greater than 25 µg/ml

Additional or Alternative Medications

If phenobarbital is not effective or not well tolerated, additional medications may be used:

Keppra® (levetiracetam): 15–20 mg/kg three times daily

Zonegran® (zonisamide): 7.5–15 mg/kg twice daily

Anticonvulsants Used Cautiously in Cats

Benzodiazepines: Long-term oral diazepam can cause idiosyncratic hepatic necrosis, a rare but often fatal reaction

Potassium bromide: Associated with coughing and shortness of breath due to suspected pulmonary fibrosis

Prognosis for Cats with Seizures

The prognosis for cats with seizures is closely related to the underlying cause of the seizures. For instance, if your cat has seizures because of a brain tumor, her prognosis will depend on how successful the treatment is. In the case of seizures with no identifiable cause (idiopathic), successful medical treatment is possible, and prognosis is generally good for a normal life with no effect on pet longevity.

Early diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression of severity and frequency is crucial to improve your cat’s lifespan.

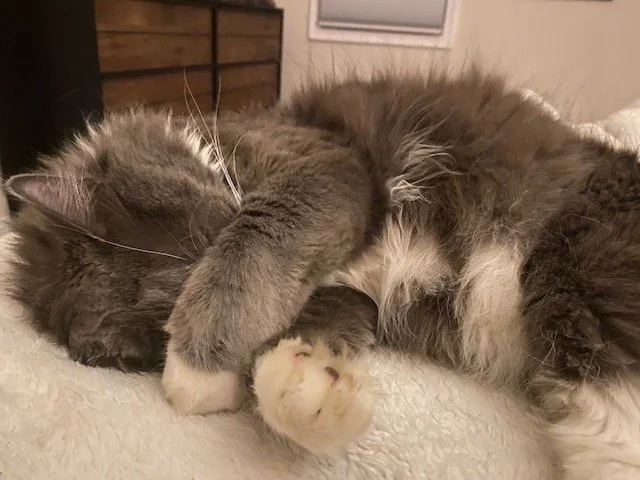

Grayson: A Case Study in Feline Seizure Management With Long-Term Medical Control

Grayson was first evaluated in 2020 after presenting to the CVRC emergency service for multiple generalized, convulsive (grand mal) seizures occurring within a single day. He experienced three seizures prior to arrival and was managed emergently by the ER team, who initiated a rapidly acting anticonvulsant that successfully stopped the seizures. Grayson was admitted for stabilization and monitoring overnight.

The following day, Grayson was transferred to the neurology service for further evaluation. At that time, he was dull, disoriented, unable to stand or walk, intermittently falling to one side, blind, and required assistance to urinate. Due to seizure clustering and severe post-ictal neurologic deficits, the case continued to be managed as an emergency.

Advanced Diagnostic Imaging and CSF Analysis for Feline Seizures

Following stabilization and a 24-hour seizure-free period, advanced diagnostics were pursued to further investigate the cause of Grayson’s severe neurologic deficits. At the time of evaluation, there were three primary diagnostic considerations:

Primary intracranial disease, such as cerebrovascular accident, infection, or neoplasia;

Typical initial effects of anticonvulsant medications administered to terminate the seizure activity; and

Seizure-related neurologic dysfunction, as animals presenting in status epilepticus can exhibit profound post-ictal neurologic signs due to the seizures themselves and the medications required to stop them. In these cases, distinguishing transient seizure effects from underlying intracranial disease can be challenging.

Once Grayson remained seizure-free for 24 hours, he was anesthetized for a brain MRI, which demonstrated normal brain architecture with no evidence of neoplasia, congenital abnormalities, or other structural disease. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was performed immediately following the MRI while he remained under anesthesia. CSF results were normal, with no abnormal cells, no evidence of neoplasia, and no bacterial or viral organisms identified. Additional infectious disease testing was also negative.

Medical Management of Seizures in Cats

Grayson was managed medically with anticonvulsant therapy. He was started on levetiracetam (Keppra®) and phenobarbital during his ICU stay. No further seizures were observed following initiation of therapy, though neurologic deficits persisted initially.

After several days of hospitalization and stabilization, Grayson was discharged on both anticonvulsant medications. His owners were counseled on seizure monitoring, medication administration, and follow-up care.

Long-Term Seizure Control and Ongoing Monitoring

Grayson remained seizure-free for six months, after which levetiracetam was tapered. In 2024, his phenobarbital dose was decreased. He has since remained stable on twice-daily phenobarbital, with annual neurologic exams and blood work remaining normal.

Outcome: Successful Long-Term Management of Feline Seizures

At his most recent recheck in December 2025, Grayson is three years seizure-free, neurologically normal, and doing well on maintenance therapy. He is expected to maintain a normal quality of life and lifespan.

Has your cat experienced seizures?

If your pet is experiencing a medical emergency, call your emergency vet immediately!

For ongoing neurology care and diagnosis of the causes underlying your cat’s seizures, we encourage you to request an appointment with our veterinary specialists for consultation and personalized care.